OUR BEST PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS

by Yalerie Douglas

The best high schools in America don't call themselves high schools at all. They are "college preparatory" schools like Andover, Exeter, Groton, and Deerfield in the East and St Mark's, Hockaday, and Jesuit in Dallas (to name only three) have forged their reputations over generations.

These schools have four things in common: challenging curricula, talented students, educated parents, and expensive tuitions.

Can students from public high schools even begin to compete against the privileged few who attend America's most famous schools? Not only can they compete, they can also excel. The five seniors from Piano Senior High who this September entered MIT - the nation's third most competitive university - are a sure sign that any public high school can hold its own against any private prep school. Of all the private schools in America, only Andover beat Piano's performance.

Private schools may have great assets, but mountains of research now reveal that only one of them really matters: a challenging curriculum. The rigor of a student's high school courses is now seen as the greatest predictor of a student's college success.

Good grades and high test scores still matter, but they don't matter as much as sheer exposure to the material. The evidence is now convincing enough to state as a rule:

Kids who take the toughest courses will do the best in college.

The toughest courses without a doubt are Advanced Placement. The AP program is national in scope and administered by the College Board, so the curriculum can't be dumbed down (always a problem with public schools). Its teachers go through extra training to teach AP courses, so they are among the most motivated - and therefore, the best - in any school. Its exams are also administered by the College Board, so the results can't be fudged or glossed over.

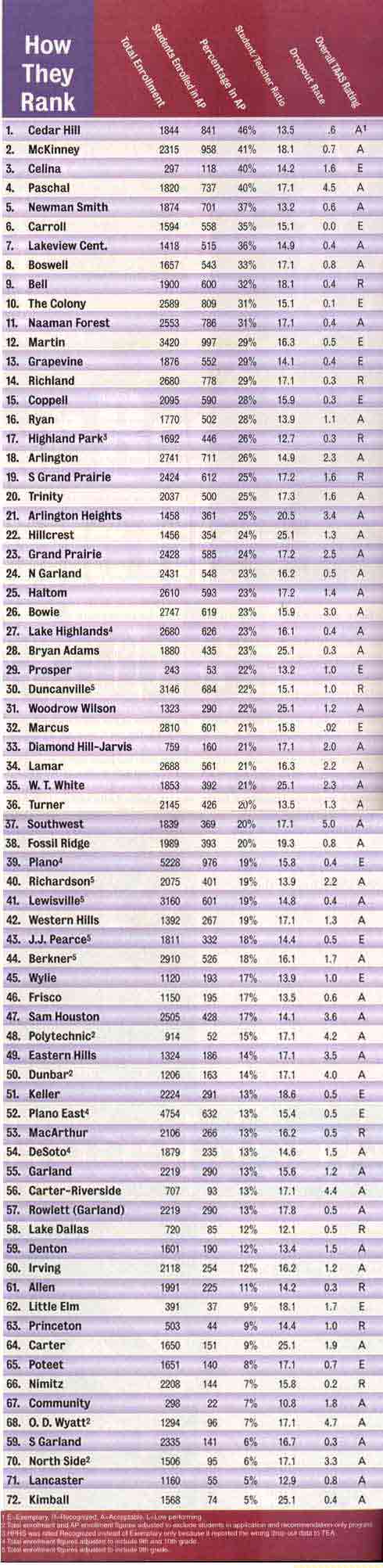

D Magazine's ranking of the best public high schools in Dallas-Fort Worth is based on this latest research. Unlike Newsweek's March ranking of high schools, which was based on number of kids in a school who took the AP test, our number is based on percentage of kids enrolled in AP. This percentage tells us how committed a school is to preparing its students for college. The statistics show that's more important and more indicative of success in college.

HOW WE SELECTED THE SCHOOLS

To qualify for the list of the top public high schools, the school had to earn an over-all average score of 70 or higher on TAAS in 2000 (disregarding minor fluctuations due to racial, socioeconomic, and attendance factors the TEA, in its wisdom, takes into account). All of our schools, with two exceptions, are "acceptable" or higher (to be "acceptable," TAAS requires an overall passing percentage of 50 or more for each section). Our two exceptions are Mansfield and Farmersville, which TAAS ranked as "acceptable" and "exemplary" respectively but didn't make our list because they do not offer AP courses. Out of the 119 schools in our readership area, 72 made our cutoff. Considering how low Texas sets the bar, that's not very encouraging. However, what's happening inside these the top rank of these 72 schools is encouraging.

Our second criterion is that the schools be truly public, that is, open to all students within their boundaries. In effect, we are recommending which schools parents should send their children to, so we recommend only schools that are open and available to everyone. Dallas magnet schools are "public" only in the sense that they are publicly funded; they are available to students only by application, and therefore didn't qualify for our list. Fort Worth mixes its special application and recommendation - only students into the general population of a school. For the purposes of this calculation, they were removed. And just to keep our apples compared to apples, in calculating the performance of the two Plano high schools, which are 11th and 12th grade only, we added in the populations of the 9th and 10th grade feeder schools. In Richardson, Lewisville, DeSoto, and Duncanville we added 9th grades.

One caveat: We relied on school districts and, in some cases, individual schools for student population and AP enrollment figures. Heritage High School in Colleyville and Mesquite ISD did not respond. Next year the TEA will make reporting of AP enrollment data mandatory for all school districts.

SURPRISE RESULTS

Cedar Hill leads our list, which will undoubtedly cause most readers to ask, "Where is Cedar Hill?" to be followed next by, "Is this a mistake?" The answer is that Cedar Hill is a small, working-class community (population: 30,000) in southwest Dallas County, and its No.1 ranking definitely is no mistake: Cedar Hill has made a big commitment to AP. Former administrator Donna Crenshaw gets the credit around town for pressing the need for AP and for getting funding from the O'Donnell Foundation. Superintendent James Rueter has worked hard to keep the support of the town's civic leadership and school board in building a high-caliber program for the district's mixed student body, which is 52 per-cent white and 48 percent minority.

The beleaguered Dallas Independent School District deserves special attention. There are 21 high schools in the DISD, not counting the magnets. Only six made our list. Most readers, including most DISD administrators, will dismiss the DISD's miserable performance with the usual excuses - blacks and Hispanics, bad parents, transients, 72 percent in the free lunch program, etc. - what George W. Bush calls the "soft bigotry of low expectations." Apparently those excuses don't wash at Carter High School, where 10 students passed the AP calculus exam, reputedly the toughest of them all.

There's another place in the DISD where low expectations have been thrown in the trash. Ranked as "low performing" by the TEA in 1999, Bryan Adams, under the leadership of principal Karen Ramos, made a schoolwide commitment - staff, students, and teachers - against mediocrity. The results are impressive: Bryan Adams somehow managed to make Newsweek's list of America's top schools in 2000, based on the number of kids who took the AP exams. How can a "low performing" school have so many kids in AP?

Bryan Adams shows what can happen to the culture of a school when AP enrollment reaches a critical mass. "Access to the curriculum itself changes things," says Highland Park's Jean Rutherford. "Students respond." Principal Ramos has rallied her school around the banner of AP. She's brought back graduates to speak to younger students about the importance of challenging themselves with the advanced curriculum. With 23 percent of the school enrolled in AP, student expectations rose and overall TAAS scores went up, bringing the school a "acceptable" ranking for 2000. Eighty percent of Bryan Adams' students now go on to college or vocational school. For those who are not college-bound, this year Ramos will introduce the vocational version of AP, a two-year Cisco computer training program leading to immediate certification.

"Frankly, it's embarrassing," says the superintendent of a more richly endowed suburban school district. "Considering where those kids [at Bryan Adams] are coming from, we should be doing 10 times better than we are.

Why aren't the tonier suburban school districts doing better? "Student and parental whining," answers one principal. He mimics the shrill voice of a complaining parent, "My little Johnny has too much work. It's too hard." The fact is, many Dallas-Fort Worth upper middle-class parents, themselves raised in an era of low expectations, have no idea how competitive the intellectual environment has become. "Kids are expected to perform at higher and higher levels," Dwight Miller, senior admissions officer at Harvard told D Magazine. Marlon Evans, assistant director of admissions at Stanford, agrees: "Students are definitely more competitive now. They bring more to the table. The ante is being raised." Notre Dame's admissions officer Dan McGinty credits AP: "The students see their friends taking AP classes and getting better prepared, then they decide to follow suit. A university wants to see students who have challenged themselves."

HOW AP WORKS

In 1951, the Ford Foundation enlisted Harvard, Princeton, and Yale and three private high schools in a study to evaluate the curriculum for the last two years of high school and the first two years of college. From that original study came the impetus for "honors" courses that eventually led to the development of a nationwide program that could be applied consistently and trusted by universities in their admissions selections.

To receive college credit for AP classes, students must pass tests administered by the Educational Testing Service, which also administers SAT, GRE, and GMAT tests. The College Board sponsors the testing program and decides how the tests will be constructed and administered.

Students can complete exit exams for the AP courses and receive college credit. Some colleges accept scores of three and up and some only accept top scores (four or five). For the 2000-2001 school year, $15 million in federal funding is available to pay test fees for economically disadvantaged students. Texas spends $10.5 million to support AP through fee subsidies, equipment grants, and school incentives. The most enticing aspect of AP for some parents is that students can place out of several entry-level college courses, saving thousands of dollars in tuition.

A College Board spokesman acknowledges this advantage of AP, but doesn't want anyone to overlook the many additional benefits. "There are some students that enter the classroom at an exceptional level and exit the classroom at an exceptional level - they are just great students. The students who struggle when they enter AP, but exit feeling prepared for the challenge of college are the real success stories - kids that might not see themselves as college material, then go on to college."

Dallas-based O'Donnell Foundation has targeted 11 area schools for an AP incentive program, giving cash grants to teachers and students. Teachers, students, and schools are encouraged and rewarded for students taking and passing the AP exams with scores of three and higher. "Vertical teams" are built within each school. Pre-AP teachers report their students' progress to junior and senior AP instructors who serve as team leaders. The pre-AP instructors also have to be trained by the College Board to teach AP classes. The pre-AP courses can identify problem areas and equip students for the challenge of AP.

Carolyn Bacon of the O'Donnell Foundation thinks of AP as a social equalizer. "People from outside Dallas have no pre-conceived notions about a school's track record. What admissions offices nationwide acknowledge is that any student that has taken AP courses is well prepared for college-level classes." Suzie Hager, of Carrollton-Farmers Branch ISD, agrees. "I've seen AP open doors for poor kids - kids that traditionally would be categorized as 'underserved.' Students who are the first in their families to even think about college need exposure to these kinds of courses before their junior and senior years of high school." That's why the O'Donnell Foundation starts building advanced programs in middle school. "When these kids get to high school," Hagar says, "they are ready for the challenges of the AP curriculum."

In Cedar Hill they certainly seem to be.

|